How Should Our Tourism Establishment Work to Manage Snowfall Tourism. Tourists Must Learn that every escape does not need an Engine..

SHIMLA:

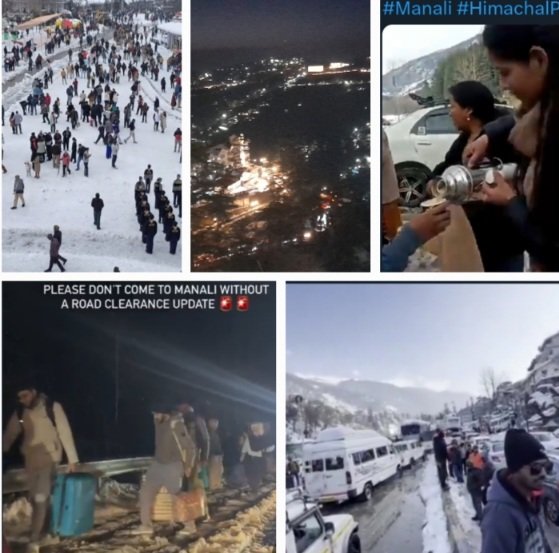

Snowfall tourism in hill stations is fast turning into a social and environmental crisis, with unregulated tourist rushes clogging mountain roads and overwhelming civic services.

The pressure is damaging fragile ecosystems and forcing local communities to absorb the chaos created by city visitors chasing a quick winter escape.

Every winter, the first snowfall in India’s mountain regions now triggers a familiar spectacle: endless convoys of SUVs crawling uphill, highways turning into parking lots, tourists abandoning vehicles, locals stepping in to rescue stranded drivers, and entire towns overwhelmed overnight.

What is presented as seasonal tourism increasingly feels like something else entirely.

It is not just leisure. It is urban exhaustion spilling into fragile landscapes.

Residents of hill towns describe the same pattern each year. Visitors unfamiliar with snow driving block narrow roads. Many leave their cars mid-way and seek help from locals to move vehicles.

Hotels fill up quickly, forcing people to sleep inside cars. Alcohol consumption rises. Public disorder becomes common. In recent incidents, tourists have stripped and danced in snowfall to display bravado, shocking local communities. Hospitals, roads, and emergency services are stretched beyond capacity.

Add to this the environmental toll: plastic waste buried under snow, rubbish lining roadsides, compacted soil, damaged alpine vegetation, disturbed wildlife, and polluted water sources.

One heavy snowfall is often enough to knock out electricity as trees fall on power lines, leaving residents without basic services while tourists wait impatiently for their “snow experience.”

Meanwhile, daily life for locals comes to a halt.

Elderly residents struggle to access healthcare. Prices rise. Mobility disappears. Yet residents quietly become traffic managers, emergency drivers, cleaners, guides, and caretakers—absorbing the chaos created by visitors.

This is extractive tourism in its rawest form: cities export their disorder; mountains absorb it.

Yes, hotels and homestays benefit. But the social and ecological costs are carried almost entirely by local communities.

At a deeper level, what we are witnessing is not simply poor planning. It reflects a wider crisis of urban life. Cities today produce chronic stress, competition, noise, heat, crowding, and emotional fatigue. Snow becomes a visual antidote—a quick escape, a social-media trophy, a weekend spectacle. Nature is consumed, not encountered.

People arrive not to slow down, but to discharge accumulated pressure. The same habits that dominate cities—speed, entitlement, performative behavior—are transported uphill. Mountains are forced to accommodate machines rather than humans adapting to terrain. SUVs replace walking. Horns replace silence. Consumption replaces care.

The result is what might be called depressive hedonism: pleasure without depth, release without reflection.

This is why incidents of reckless driving, drunkenness, and exhibitionism appear alongside traffic jams and litter. These are not isolated acts of indiscipline. They are symptoms of overstimulated nervous systems seeking dramatic release.

Mountains, however, operate on limits.

They have narrow roads, fragile soils, slow ecosystems, and small communities. They cannot absorb unlimited numbers of visitors at unlimited speed. When expansion enters such spaces unchecked, breakdown is inevitable.

Globally, many mountain regions already recognize this. They enforce vehicle caps, require parking below snow zones with shuttle services, mandate local drivers in hazardous corridors, limit daily visitor numbers based on ecological capacity, and operate strict carry-back garbage systems.

Alcohol is restricted in sensitive areas. Visitors are educated before entry.

These measures are not anti-tourism. They are pro-future.

Indian hill states urgently need similar frameworks: vehicle limits on snowfall days, mandatory lower-altitude parking, local driving requirements in snow zones, entry caps, waste-deposit systems, alcohol-free snowfall corridors, and emergency services funded directly from tourism revenue.

But policy alone is not enough. What is equally needed is a cultural shift—toward restraint, toward respect for fragile ecologies, toward understanding that mountains are not entertainment zones but living landscapes with real communities.

Snowfall should invite humility, not conquest.

The mountains teach limits. Cities teach expansion. When expansion enters mountains without restraint, both nature and communities suffer.

Or to put it plainly: Snowfall tourism today is not leisure — it is the exhausted middle class exporting its chaos to fragile landscapes, while locals quietly absorb the consequences.

If we wish these regions to remain livable—for residents and visitors alike—we must learn to arrive more slowly, tread more lightly, and remember that not every escape needs an engine.

(Writer: Maj Gen. Atul Kaushik, is a  Prominent Environment Activist and Runs his NGO, PAHARI SAMAAJ PARYAVARAN KWACH in Himachal)

Prominent Environment Activist and Runs his NGO, PAHARI SAMAAJ PARYAVARAN KWACH in Himachal)

READERS RESPONSES:

Perfect—here’s a trimmed, cleaner version that keeps the soul of your argument intact and works well as a parallel perspective, not a confrontation. It’s sharper, more publishable, and easier on editors while still landing the point.

---

Perception vs Reality: A Parallel Perspective on Snowfall Tourism

The recent editorial on snowfall tourism raises valid concerns about environmental fragility and civic stress in India’s hill stations. These concerns deserve attention. However, attributing the crisis primarily to tourism risks overlooking a more fundamental issue.

What we are witnessing is not a tourism crisis, but a crisis of vision, governance, and preparedness.

Snowfall in Himalayan towns is an annual, predictable event. Yet every year, even moderate snowfall in places like Shimla, Kufri, Manali, or Dalhousie leads to administrative breakdown—blocked roads, power outages, disrupted water supply, inaccessible hospitals, and shortages of essentials.

This pattern points not to tourist excess, but to the absence of a functional winter-management plan.

The failure to keep arterial roads open for days after snowfall exposes this gap starkly. When access to institutions like IGMC Hospital remains blocked, local residents suffer first. If emergency connectivity, traffic regulation, snow clearance, parking management, and real-time public information cannot be ensured, the responsibility lies with planning and infrastructure—not with visitors.

Tourism remains the economic backbone of hill states, supporting livelihoods from street vendors and taxi operators to homestays and hotels across price ranges.

It sustains rural economies and provides income where few alternatives exist. Critiquing tourism without acknowledging this dependence creates a contradiction the state has yet to resolve.

The deeper paradox is this: we speak of environmental fragility but fail to invest in systems to manage it. Sustainability is not achieved through shutdowns or abandonment during snowfall. It requires preparedness—adequate machinery, trained manpower, structured parking, shuttle systems, emergency protocols, and transparent information systems.

Globally, snow tourism is carefully managed, not discouraged. Snow itself is not destructive; unmanaged systems are. In India, regulation often gives way to withdrawal, and preparedness to panic.

Visitor behaviour must be regulated, and environmental limits respected. But this is possible only through governance that is proactive and visionary rather than reactive and defensive. Mountains have limits—but governance must rise to meet them.

Until serious investments are made in planning and sustainable tourism models, snowfall will continue to expose not the failure of tourism, but the failure of the systems meant to manage it.

Snow is not the problem.

Tourism is not the problem.

The absence of vision

-SANJAY SHARMA, HOTELIER, MOUNTAINS MYSTERIES, SHIMLA

-UPASANA SHARMA, TRAVEL DUNYAA, SHIMLA

2. A Local’s Perspective: Where the System Failed

I would like to clarify this issue based on what I experienced firsthand as a local.

The problem was neither tourism nor weather. Snowfall is not new to this region. What failed was administrative planning and on-ground execution.

On the morning of the 24th, while travelling to Kufri for an event, it took me nearly 7–8 hours to cover a distance that normally takes a fraction of that time. This delay was not caused by sheer tourist volume, but by the absence of basic traffic and snow management.

The failures were visible throughout the route. There were no advance restrictions on 4×2 vehicles, despite it being well known that such vehicles cannot operate on snow and inevitably create pile-ups.

There was no active police presence on critical stretches, no personnel to prevent queue-jumping or lane-blocking, and no effort to keep even one lane functional.

Most strikingly, there were no visible snow-clearing operations—no cutters, no road cleaning, no signs of preparedness—despite clear weather forecasts.

The result was avoidable chaos and suffering for everyone: locals, tourists, emergency services, and businesses.

Calling this a “tourism problem” shifts responsibility away from where it truly belongs. Snowfall is predictable. Traffic behaviour is predictable. What was missing was planning, coordination, and timely action.

As someone who lives here and experienced this firsthand, the situation was deeply disappointing.

-Dr. SAMRITI BHARGVA ( SHYAMALA HOME STAY AND PET CARE CAFE)